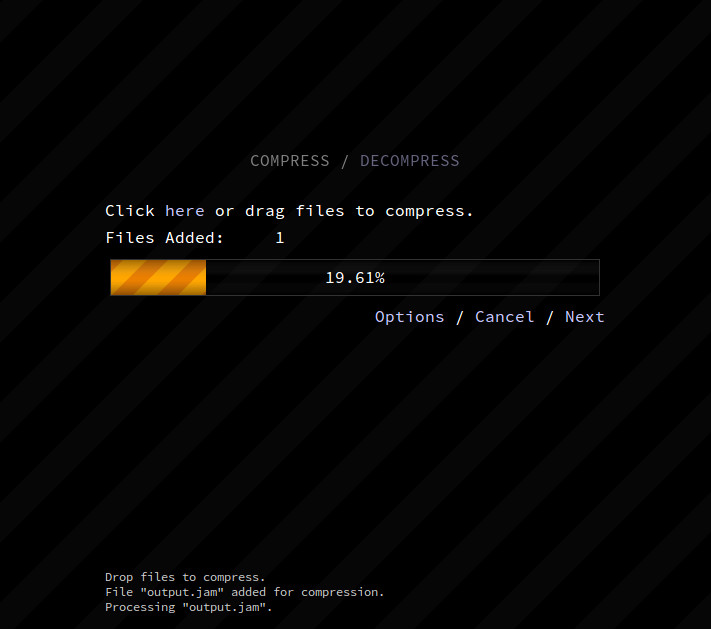

After reading about the sequitur algorithm, I was keen to implement it and see if I could create my own web based file compressor. You can have a play with the results of my work here.

Introduction

Cutting straight to the chase, here are the different pieces of the file compression program:

- The compression algorithm(s).

- A bit stream reader/writer, to read and write individual bits.

- A core, which makes use of the above. This compresses/decompresses blocks of data, as well as appends file information and details about the compressed blocks to make decompression possible.

- A front facing object which talks to the compression core, and sends/receives input/output data from the web interface.

Two separate compression algorithms were implemented in the application. Both algorithms read 8 bits of input at a time, leading to a total of 256 different input symbols. The first, and primary algorithm was based on Sequitur.

Sequitur

The Sequitur algorithm was used to extract repetition from the input as it was fed in, and generate rules, each of which represented a portion of repetition. Rules were then pruned based on their utility in helping to compress the file, which was determined by rule_length x number_of_times_used. So, a higher utility value meant that rules had to account for more input characters in order to be kept. As each rule adds an additional symbol, and more different symbols means more bits needed per symbol on average, pruning rules helps to remove those which don't contribute enough to the compression. Read more about Sequitur in my other post here.

After we have arrived at a number of rules, each being equal to a sequence of inputs that happens to repeat itself in the input data, we convert each symbol into a binary string (that is, a string of 1's and 0's) using Huffman Coding. This helps reduce the number of bits used to represent each symbol. We then encode the Huffman tree required to decode these binary strings, and the Sequitur rule index, and stick these onto the compressed block of data.

BWT with MTF

The other compression algorithm available is actually a combination of the Burrows-Wheeler Transform, and the Move to Front Transform.

The Burrows-Wheeler Transform

Briefly, BWT transforms the data in such a way that repeated characters tend to be next to eachother. It does this by taking all of the possible rotations of an input sequence, sorting them alphabetically, and then returning the last column. Here is an example (adapted from wikipedia):

Input: BANANA

rotations (adding an e for end of file):

BANANAe

eBANANA

AeBANAN

NAeBANA

ANAeBAN

NANAeBA

ANANAeB

alphabetically sorted rotations:

AeBANAN

ANAeBAN

ANANAeB

BANANAe

eBANANA

NAeBANA

NANAeBA

Last column (output): NNBeAAA

Keeping track of the end of file is important for reconstructing the original input, but rather than using a symbol as I have done above, the location of it can be stored separately. It is also important to sort the entire strings alphabetically, not just the first character of each string.

Implementation wise, you do not actually need to store an array containing all of the possible rotations, but instead can just use references to positions in one string, and rotate around the string when you reach the end of it (until you get back to the starting point). This way, you just need to sort the references themselves into the correct order, and can output the last column by taking the character one before each reference.

A rather inefficient way to reverse the transformation is made possible by the fact that, by sorting the output, we obtain the column one rotation around (in other words, the first column of the sorted rotations seen above). Joining them results in:

NA

NA

BA

eB

Ae

AN

AN

Where the original output string is the first column, and the sorted version of it is the second column. Sorting this, we actually end up with the first and second row of the sorted rotations:

Ae

AN

AN

BA

eB

NA

NA

Since we know what the last row is still, we can now add that onto the front again and sort once more. In doing so we end up with the first three rows like so:

AeB

ANA

ANA

BAN

eBA

NAe

NAN

By repeating this process, we can build up the entire sorted rotations table once again, and knowing where the end of file marker is, we can output the original word! Pretty neat, huh? There are however much faster ways to perform this reverse. Although I have implemented such a method, it's far less intuitive to explain, and frankly I can't remember exactly how it works now!

The Move to Front Transform

The MTF transform steps in next, and capitalizes on the increase in repetition by representing repeated sequences in terms of low value outputs. Essentially, it does the following:

Create a list of all possible symbols

For each symbol seen in the input

locate that symbol in the list

output the position of that symbol in the list

move that symbol to the front of the list

So, consider the list bananaaa (example taken from wikipedia), read one character at a time:

| Input | Output | List |

|---|---|---|

| b | 1 | abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz |

| a | 1,1 | bacdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz |

| n | 1,1,13 | abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz |

| a | 1,1,13,1 | nabcdefghijklmopqrstuvwxyz |

| n | 1,1,13,1,1 | anbcdefghijklmopqrstuvwxyz |

| a | 1,1,13,1,1,1 | nabcdefghijklmopqrstuvwxyz |

| a | 1,1,13,1,1,1,0 | anbcdefghijklmopqrstuvwxyz |

| a | 1,1,13,1,1,1,0,0 | anbcdefghijklmopqrstuvwxyz |

We can see that, even with 26 possible characters, the repetition in the phrase leads to an output consisting of repetition of low values. Converting back to the original input symbols, we'd end up with an output phrase of bbmbbbaa, which can easily be reversed.

The advantage of doing this comes into play when Huffman Coding is used to convert the 8 bit characters into binary strings. As Huffman Coding uses shorter binary strings to represent more frequently occurring symbols, the MTF output is often represented more compactly than it would be if MTF was not performed. An alternative (or addition) to MTF would be Run Time Encoding, which works by representing any characters seen in sequence more than a certain number of times with one (sometimes more) instance of that character, followed by a number indicating how many times it has been seen.

So, BWT is used to increase the amount of repetition. MTF then increases the frequency of low value characters as a result of this repetition, and then finally Huffman Coding is used to efficiently represent this.

The Compression Core

The compression core is fed a stream of data, and asks the compression algorithm specified to compress it until a certain amount has been compressed (one blocks worth). At this point, the compression algorithms finalize the compression of that block by appending the Huffman tree or any other relevant data to the block. It then asks for the next block worth of data, and repeats the process until all data has been compressed.

Once everything has been compressed, the core appends the relevant data to the set of blocks and outputs them (how many blocks there are, and in which positions the different files are is most relevant). The compression core works in a separate thread (using a Web Worker), and so does not interfere with the UI. It is sent commands and data by the compression front-end, which is connected to the UI.

Performance

By splitting the compression into blocks of a fixed size, each block requiring about the same time as the last, both algorithms end up working in linear time when large files are considered. That is, the time they take is proportional to the size of the file. Sequitur works in linear time for any block size, however its memory requirements (especially in Javascript) increase to an unmanageable size if the block size is too large (on my machine, I have issues around 30 megabytes). BWT+MTF compression performs worse than linear time, as sorting the rotations in the BWT step can not be done in linear time. In addition, depending on the input, the time taken to perform the sort can differ vastly, as illustrated below. IT is however less memory intensive than Sequitur.

A couple of very rough benchmarks using the default block size of 2000kb:

10.5meg binary:

Sequitur: 166s compress, 41.8s decompress, output 5.2megs

BWT+MTF: 67.6s compress, 17.3s decompress, output 4.5megs

5meg bacteria genome:

Sequitur: 64.4s compress, 17.2s decompress, output 1.2megs

BWT+MTF: 19.2s compress, 5.4s decompress, output 1.2megs

8.3meg BMP image:

Sequitur: 106s compress, 17.2s decompress, output 1.1megs

BWT+MTF: Ages (it did not finish in any reasonable time)

We can see that performance varies, although decompression is always quicker than compression. In the last example, the BWT part of the algorithm was left sorting 2 million identical strings (as the top part of the image was entirely white). This meant it had to check every string in its entirety, so it did not come close to finishing before I cancelled it.

Having been written in Javascript, and using arrays of symbols to store binary data (though this could be optimised by using ArrayBuffers), the algorithms are of course significantly slower and more memory intensive than any native compression ones. That said, I'm sure that there are various means to optimise the code (representing binary strings in a more efficient manner for instance).

Summary

This has been a fun exercise as I got to play with a bunch of really clever algorithms, and experiment with bashing them together to see what the result would be. While not usable in the real world, it's pretty nifty, and can even outperform regular zip compression in some cases (though you may need to tweak the settings to really get that). You can have a play with the finished project right here. The rule based approach employed in Sequitur is not too dissimilar to that used in various modern compression algorithms, which can use various layers of different algorithms to achieve the optimum compression, including those mentioned above.